One of Mars's most striking features is also one of its biggest mysteries. If you look at a map of the Red Planet, you'll notice something odd: the northern half sits about 3 kilometers lower than the southern half. This dramatic difference, called the Martian dichotomy, has puzzled scientists for decades.

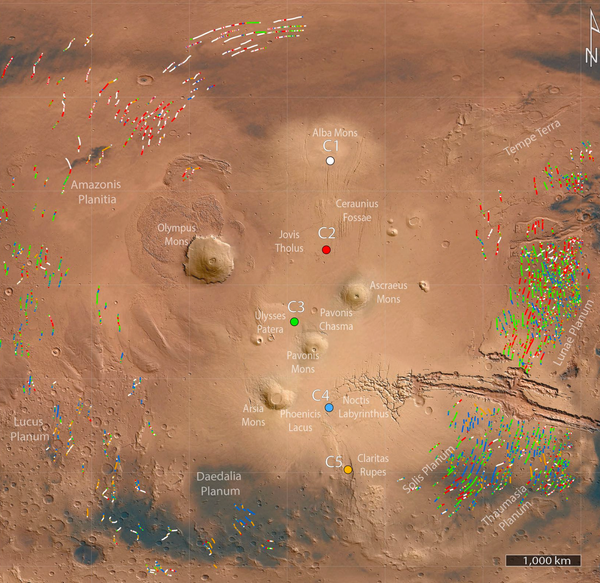

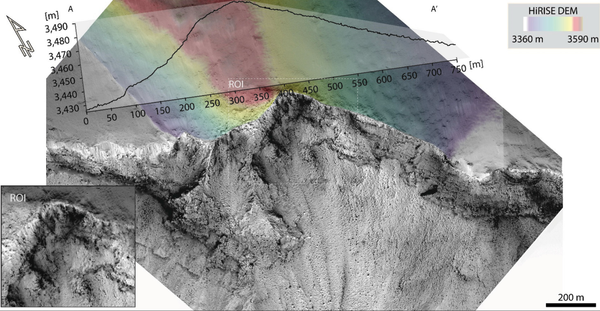

But here's what makes it even more intriguing—in one specific region called Nilosyrtis Mensae, we found something unusual. There are extensional faults (think of them as cracks where the ground pulled apart) running along the boundary between the high and low regions, and about 800 kilometers away into the lowlands, there are compressional ridges (where the ground was pushed together). Both sets of features run roughly parallel to each other.

This pattern looked strangely familiar to me and my colleagues. It resembles what we see on Earth along passive continental margins—places where gravity causes the land to slowly slide downslope, creating extension at the top and compression at the bottom. But could this really happen on Mars? And if so, what would it tell us about the planet's history?

Why We Turned to Numerical Models

To answer these questions, we couldn't just look at satellite images. We needed to test whether gravity-driven deformation was physically possible under Martian conditions, and if so, what kind of subsurface structure would be required to make it work.

This is where numerical modeling became absolutely essential. Think of it as building a virtual Mars inside a computer—one where we can control the laws of physics, test different rock types, and watch millions of years of deformation happen in hours.

Setting Up Our Virtual Mars

We used a sophisticated code called Norma to run our simulations. The challenge was to recreate a 700-kilometer-wide slice of Mars extending 20 kilometers deep, with enough resolution to capture the details of fault formation. Our model contained about 4 million markers tracking different rock properties as they moved and deformed over time.

The setup itself required careful thought. We started with:

- A 4-kilometer-thick upper layer of basaltic rock (representing the Martian crust)

- A 1-kilometer-thick detachment layer (the weak zone that would allow sliding)

- Another 4-kilometer layer of lower crust

- A low-density "sticky air" layer on top to simulate a free surface

The tricky part was getting the rock properties right. Mars isn't Earth, so we had to account for:

- Martian gravity (3.72 m/s², about 38% of Earth's)

- Martian crustal densities (around 3000 kg/m³)

- The correct viscosity for different rock types

- How rocks fail under stress

Testing Three Different Scenarios

Here's where the modeling really proved its worth. We didn't just run one simulation—we ran three fundamentally different scenarios to see which one matched what we observe on Mars today.

Model 1: A Frictional Detachment Throughout

In our first model, we simulated a detachment layer made of overpressured clay or shale-like material throughout the entire system. We gave it a relatively high fluid pressure ratio (λ = 0.9) to make it weak enough to deform.

The results were disappointing but informative. Deformation got stuck near the dichotomy boundary. Extension happened along the scarp, sure, but it couldn't propagate far into either the highlands or the lowlands. After just 2 million years of simulation, the system essentially locked up. We might have gotten some faulting near the boundary, but nothing like the 800-kilometer-wide system we see in nature.

The viscosity of this frictional layer, even with high fluid pressure, stayed around 10²¹ Pa·s—still too high to allow the kind of distributed deformation we needed.

Model 2: A Weak Viscous Detachment Throughout

For our second model, we went to the other extreme: a very weak, viscous-like detachment with a viscosity of just 10¹⁷–10¹⁸ Pa·s running continuously under both the highlands and lowlands. This could represent salt, ice, or a mixture of both with fractured basalt.

This model was much more successful at creating deformation across the entire system. Extension started almost immediately (within 0.03 million years of simulation time) near the dichotomy, then spread both backward into the highlands and forward into the lowlands.

The compressional domain developed nicely, with thrust faults forming in an "out-of-sequence" pattern—meaning the front faults formed first, then new faults developed progressively backward toward the highlands. By 5 million years, we had clear extensional, transitional, and compressional domains.

But there was a problem. The model created two distinct topographic steps in the highlands, and that's not what we see on Mars. The extensional domain was also too long compared to observations.

Model 3: Two Different Detachments

Our third model was the winner. We combined both approaches: a shallower frictional detachment in the highlands connected to a deeper viscous detachment in the lowlands.

This is where the numerical modeling really showed its power. The model revealed how these two detachment layers could link up through a "relay zone" right at the dichotomy boundary. The strain patterns told a compelling story:

- For the first 4.5 million years, most deformation occurred in the highlands as normal faults formed

- Then there was a shift—extension decreased in the highlands but picked up in the nearby lowlands

- By 13.5 million years, the frictional detachment in the highlands was essentially done moving

- The compressional domain, meanwhile, showed that characteristic out-of-sequence development, reaching its maximum width around 13.35 million years

- By 20 million years (our simulation end time), the system had stabilized

The final topography from Model 3 matched observations beautifully: a single lowered slope near the dichotomy, a wide low-relief bulge in the transitional zone, and a series of ridges in the compressional domain.

What the Numbers Told Us

When we compared the three models quantitatively, the differences were stark. We looked at the normalized lengths of the three structural domains:

- Model 1 (frictional only): 100% extensional domain, 0% transitional, 0% compressional

- Model 2 (viscous only): ~20% extensional, ~30% transitional, ~50% compressional

- Model 3 (combined): 14% extensional, 68% transitional, 18% compressional

The real Mars sections we mapped averaged: 24% extensional, 46% transitional, 30% compressional.

Model 3 was clearly the closest match, especially considering that erosion and burial on Mars would have obscured some of the extensional features, making that domain appear smaller than it originally was.

The viscosity contrast between the two detachment types was also crucial. The frictional detachment never got below about 10²¹ Pa·s even with high fluid pressure, while the viscous detachment was 10¹⁷–10¹⁸ Pa·s—about 1,000 to 10,000 times weaker. This difference of several orders of magnitude was necessary to produce the observed pattern.

What This Means for Mars's History

The numerical modeling didn't just show us that gravity-driven deformation was possible—it revealed what had to exist beneath the Martian surface for it to work.

The need for two different detachment types tells us something profound about Mars's early history. Here's the story that emerges:

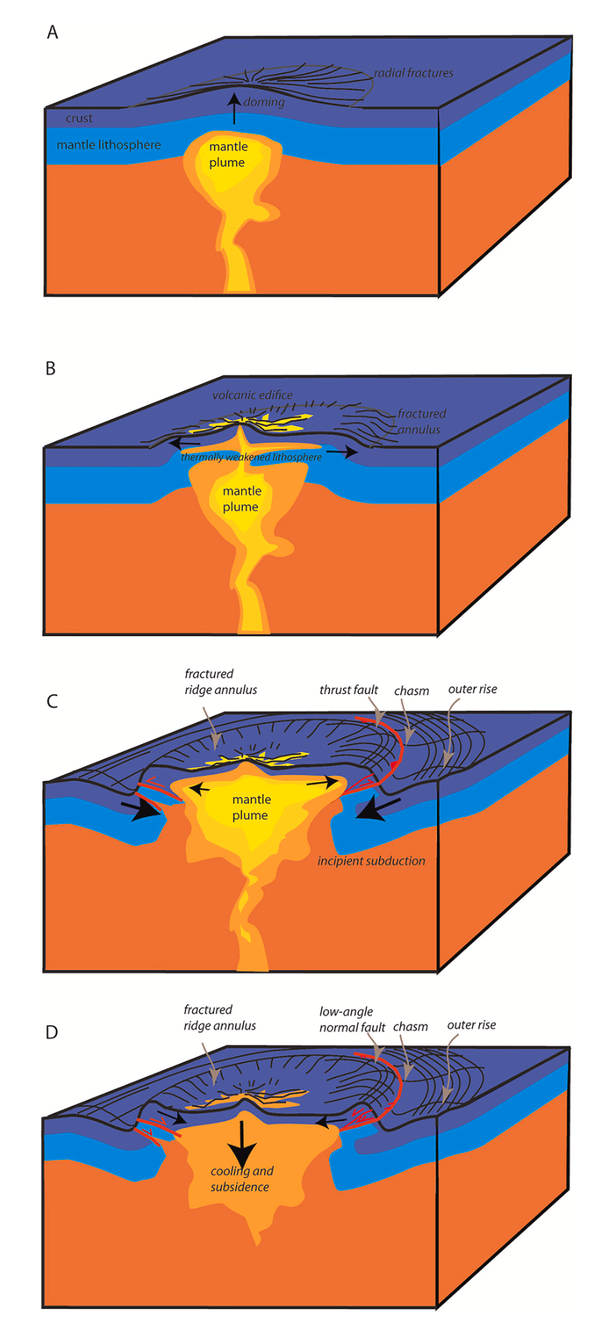

About 4.5 billion years ago, a giant impact (the "Borealis impact") created the northern lowlands. This impact excavated much of the pre-existing crust and created an enormous impact melt pool. As this cooled and a shallow, short-lived ocean formed, evaporites (salt minerals) precipitated out. Later impacts, particularly the Utopia impact around 4.1 billion years ago, churned up and redistributed this salt within a thick layer of fractured basalt (megaregolith).

The result? A mechanically weak layer 5-11 kilometers deep—perfect for acting as a detachment surface.

Meanwhile, in the highlands, volcanic activity laid down flood basalts with thin sedimentary layers in between, creating pockets of overpressured fine-grained material that could act as a frictional detachment.

Then, around 3.8-3.6 billion years ago (Late Noachian to Early Hesperian), something triggered the system. Perhaps it was the Tharsis volcanic region growing and shifting Mars's entire crust, or the Isidis impact, or regional uplift. Whatever the trigger, gravity took over.

Our models show this happened relatively quickly—the entire system evolved in perhaps 20 million years, maybe less. The dichotomy boundary failed, the highlands started sliding northward, and the system ran its course, creating the features we see today before erosion and volcanic resurfacing partially buried the evidence.

Why Numerical Modeling Was Essential

Let me be clear: we couldn't have figured this out without numerical modeling. Here's why:

1. Testing what we can't see: The detachment layers are buried kilometers deep. No amount of satellite mapping could tell us whether they exist or what they're made of. But the models showed us what must be there to produce the observed structures.

2. Testing physical plausibility: It's one thing to draw a cross-section that looks nice. It's another to prove that it can actually form under real physical conditions. The models incorporate actual rock mechanics, realistic viscosities, and proper gravitational forces. If something can't work in the model, it probably can't work in nature.

3. Understanding timing: The models revealed that this wasn't a slow, steady process but rather had distinct phases—early extension, a shift in strain patterns, peak compression, then stabilization. This temporal evolution would be impossible to reconstruct from surface observations alone.

4. Quantifying requirements: The models told us precisely how weak the detachment layers needed to be. A viscosity contrast of 1,000-10,000 times between the highland and lowland detachments wasn't just helpful—it was necessary. That's a concrete constraint for understanding Mars's subsurface composition.

5. Ruling out alternatives: Just as important as showing Model 3 worked was showing that Models 1 and 2 didn't. Science advances by elimination as much as confirmation.

The Bigger Picture

This work demonstrates that Mars and Earth share more geological processes than we might have thought. Gravity-driven fold-thrust belts are common on Earth along passive continental margins like the Gulf of Mexico or the coast of Angola. The wedge angle we calculated for Mars (~0.4°) matches nicely with Earth examples, particularly the Angola margin.

But there's a key difference: on Earth, these systems typically form in marine sediments as continental margins subside. On Mars, we're looking at a system that formed in impact-related materials and ancient ocean sediments, driven by the unique conditions of early Martian history.

The numerical modeling also provided a bonus insight: it supported the giant impact origin for the northern lowlands. Without that impact to create the mechanically weak layer in the lowlands, the gravity-driven system couldn't have worked the way our models showed it did.

What's Next?

This research opens up new questions. If salt-rich layers exist this deep in the Martian lowlands, what does that mean for:

- Other tectonic features on Mars?

- The history and composition of early Martian oceans?

- Potential resources for future Mars missions?

NASA's InSight lander has already detected seismic discontinuities in the lowland crust at depths of 8±2 kilometers—remarkably consistent with our model predictions. Future seismic studies could help confirm the presence and nature of these weak layers.

For me, this project highlights why numerical modeling is such a powerful tool in planetary science. Mars doesn't have plate tectonics like Earth, but it has had a dynamic geological history. Computer models let us run experiments we could never do in a lab or field, testing ideas about events that happened billions of years ago on a planet we've never visited.

Every time we run a new simulation, we're essentially asking Mars, "Could this have happened?" The answer, for gravity-driven deformation at Nilosyrtis Mensae, appears to be yes—and the story it tells is fascinating.

This research was published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters. The numerical simulations were performed using the Norma code, a finite-difference mechanical modeling framework specifically designed for studying tectonic processes.