A Giant Volcanic Mystery on the Red Planet

Mars's Tharsis region is hard to miss—it's a massive volcanic bulge spanning roughly 6,000 kilometers across and rising over 20 kilometers high. Think of it as a dome the size of North America, piled high with volcanic material accumulated over 4 billion years. For decades, scientists have wondered: what caused this enormous feature? And more intriguingly, did the volcanic activity shift location over time?

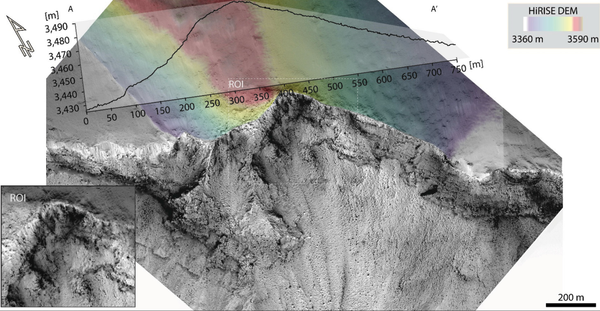

Our research team tackled these questions by studying wrinkle ridges—those peculiar wave-like features that ripple across Mars's surface like wrinkles in a rug. These aren't just interesting geological quirks; they're actually frozen records of ancient stresses that squeezed and compressed the Martian crust as Tharsis grew.

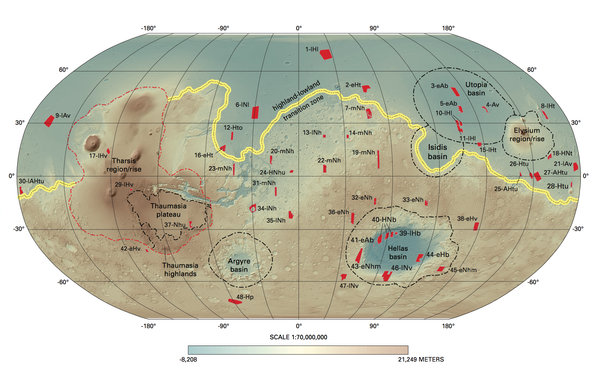

Mapping 77,000 Kilometers of Martian Wrinkles

We embarked on an ambitious project: meticulously mapping 650 individual wrinkle ridges stretching a combined 77,294 kilometers across Mars's western hemisphere. To put that in perspective, that's nearly twice the circumference of Earth! We broke these ridges down into 34,741 smaller segments, each about 2 kilometers long, and analyzed them using high-resolution images and elevation data.

The key insight? If these ridges formed due to stress from a rising plume of hot material beneath the crust, they should curve in a roughly circular pattern around the stress source—like ripples radiating from where you drop a stone in water. By analyzing how each ridge segment deviates from a perfect circular pattern, we could pinpoint where the stress originated.

Five Stress Centers Tell a Story of Migration

Our analysis revealed something remarkable: not one, but five distinct stress centers scattered across the Tharsis region:

- C1: Near the southern edge of Alba Mons caldera in the north

- C2: Between Jovis Tholus and Ceraunius Fossae

- C3: Between Ulysses Patera and Pavonis Chasma

- C4: At Phoenicis Lacus, near Noctis Labyrinthus

- C5: At Claritas Rupes in the south

These centers stretch across 4,518 kilometers from north to south—evidence that the source of volcanic stress migrated over geological time rather than remaining fixed in one spot.

Reading the Timeline: Which Came First?

But finding five centers wasn't enough—we needed to know the order in which they were active. This is where detective work came in. Just like a crime scene investigator looks at which bloodstains are on top of others, we examined where wrinkle ridges cross-cut each other. When one ridge cuts across another, the cutting ridge must be younger.

After painstakingly examining dozens of these intersections, we reconstructed the sequence: C2 → C3 → C1 → C4 → C3 (again) → C5 → C4 (again)

This pattern reveals something fascinating: the stress didn't just march steadily from north to south. Instead, it jumped around, with some centers reactivating multiple times. The C4 center, in particular, appears to have been the most recently active location.

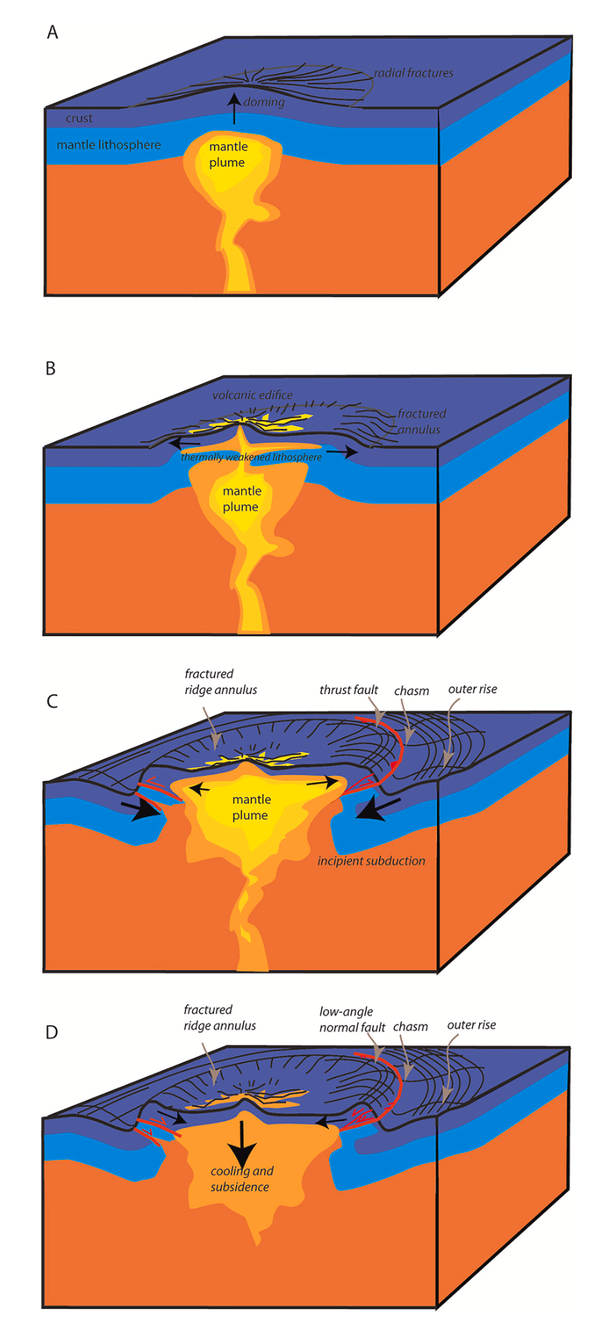

The Critical Taper: Mars as a Gently Sloping Wedge

Here's where our research gets even more interesting. We didn't just map where the ridges are—we calculated what lies beneath them. Using the ridges' heights and widths, we estimated how much the crust shortened (between 1.5 to 3.8 kilometers along different profiles) and how deep the faults extend beneath the surface (between 2.9 and 8.8 kilometers).

When we plotted these detachment depths against distance from each stress center, a clear pattern emerged: both the surface topography and the buried faults form a very gentle wedge shape, with angles between just 1.2° and 2.2°. This is incredibly shallow—much gentler than Earth's mountain belts.

This wedge shape is significant because it follows what geologists call "critical taper theory"—the same principle that explains how Earth's fold-and-thrust mountain belts form. The Tharsis dome essentially acted like an enormous accretionary wedge, with material being pushed outward and upward by the rising plume below.

The Water Beneath: An Unexpectedly Slippery Layer

Perhaps our most intriguing finding concerns what must have been lubricating these faults. The extremely gentle wedge angles we calculated require unusually low friction along the detachment zones—much lower than typical rock-on-rock sliding.

We calculated friction coefficients ranging from just 0.055 to 0.093. For comparison, normal rock friction is usually around 0.6 to 0.85. Something was dramatically reducing the friction.

Our interpretation? Liquid water trapped beneath an impermeable permafrost layer.

Here's how this would work: The detachment depths we calculated (3-9 km) coincide with depths where Mars's internal heat would keep water liquid despite the cold surface. Above this zone, frozen ground (permafrost) would act as a seal, preventing the water from escaping upward. The pressure of the overlying rock would build up fluid pressure below, effectively "floating" the upper crust and allowing it to slide much more easily.

Alternative possibilities include layers of clay minerals or salt deposits, both of which are known to exist on Mars and can also act as lubricants. The presence of evaporite deposits (like sulfates) in nearby Valles Marineris canyons supports this possibility.

What It All Means: A Migrating Plume Beneath Ancient Mars

Our findings paint a picture of Tharsis's formation that's more complex and dynamic than previously thought:

- The plume wasn't stationary: Rather than a single fixed hotspot, volcanic activity migrated across the region over hundreds of millions of years, between the Late Noachian and Early Hesperian periods (roughly 3.7-3.1 billion years ago).

- Multiple reactivations occurred: The stress centers didn't just activate once and shut off—C3 and especially C4 reactivated, suggesting either plume branching or back-and-forth movement of the main plume.

- Water played a crucial role: The weak detachment zones we identified suggest liquid water was present at depth during ridge formation, trapped beneath an icy lid and helping to facilitate crustal deformation.

- The overall motion was northward to southward: Despite the complexity, there's a general trend of stress center migration from north (C2, C1) toward the south (C4, C5), with C4 representing the final major phase of activity.

This migration might reflect the plume's interaction with variations in crustal thickness, particularly near Mars's dramatic hemispheric boundary (the dichotomy) where the northern lowlands meet the southern highlands. The thick crust in the south might have channeled or blocked the plume, causing it to branch or shift position.

Why This Matters

Understanding Tharsis isn't just about Martian geology—it's about understanding how an entire planet works. Tharsis dominates Mars's topography, affected its rotation, influenced its climate, and may have played a role in whatever water once flowed on the surface.

Our work provides the most detailed reconstruction yet of how this enormous feature evolved, revealing a history far more dynamic than previously suspected. The five stress centers, their migration pattern, and the low-friction detachments all point to a complex interplay between rising mantle plumes, crustal structure, and subsurface fluids.

It's also a reminder that even "dead" planets have remarkably complex geological histories. Mars hasn't seen significant volcanic activity for millions of years, but the wrinkle ridges preserve a detailed record of its violent volcanic past—if you know how to read them.

This research was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets by Oguzcan Karagoz, Thomas Kenkmann, and Stefan Hergarten from Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Germany.