If you've ever looked at images of Mars, you might have noticed these long, sinuous ridges snaking across the surface. Scientists call them "wrinkle ridges," and while they might look like simple bumps from orbit, they're actually windows into some fascinating geology happening beneath the Martian surface.

In my previous research, I studied how these ridges form and what they tell us about ancient stresses in the Martian crust. But one big question remained: what do these structures actually look like underground?

A Rare Opportunity

The challenge with studying planetary geology is obvious—we can't exactly dig trenches on Mars to see what's beneath the surface. But nature sometimes does the excavation for us. Impact craters, collapse pits, and ancient valleys occasionally cut right through wrinkle ridges, creating natural cross-sections that expose the subsurface structure.

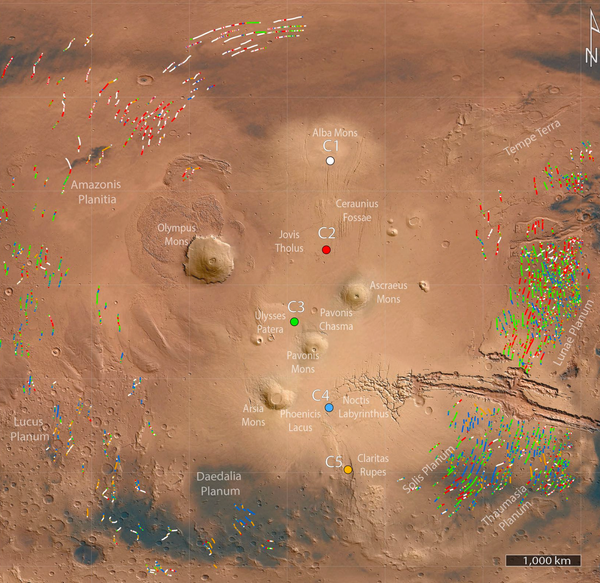

For this study, I hunted for these rare exposures across the Tharsis region of Mars, focusing on twelve sites where deep cuts—some reaching 500 to 1000 meters below the surface—revealed the hidden architecture beneath wrinkle ridges.

What We Found Underground

Using high-resolution images from Mars orbiters, we mapped the complex patterns of faults beneath these ridges. What emerged was a picture far more intricate than simple surface buckling.

The Fault Patterns

The subsurface is dominated by thrust faults and reverse faults—fractures where one block of rock has been pushed up and over another. Here's the key distinction: we call it a "thrust" if the fault dips at less than 45 degrees, and a "reverse fault" if it's steeper than 45 degrees. Both types are common beneath wrinkle ridges, and often both are present in the same structure.

One of the most consistent findings was that asymmetric wrinkle ridges have a dominant fault system on one side. The main thrust fault typically reaches the surface right at the base of the steeper slope of the ridge. It's like the ridge is sitting on top of a ramp that's tilting everything to one side.

We measured the dip angles of these faults wherever we could find planar sections exposed in crater walls or cliff faces. On average, the primary thrust faults dip at about 37° ± 2°, while associated backthrusts (faults dipping in the opposite direction) are slightly shallower at 28° ± 2°.

The Listric Shape Discovery

One of the most interesting findings was that many of these faults don't maintain a constant angle as they go deeper. In nine out of our twelve study sites, we observed that faults start out fairly steep near the surface but bend over to shallower angles at depth—typically somewhere between 500 and 1000 meters down.

This "listric" shape (curving from steep to shallow) is significant. It suggests these faults might be connecting to a nearly horizontal weak layer deeper in the crust—what geologists call a detachment zone.

Complexity and Subsidiary Faults

Most wrinkle ridges aren't formed by a single, clean fault. Instead, they're characterized by a multitude of subsidiary and splay faults—smaller faults that branch off from the main structure. These create the characteristically "wrinkled" appearance that gives these features their name. It's a bit like how a rug bunches up when you push it across the floor—you don't get one clean fold, but rather a complex pattern of smaller wrinkles and folds.

Folding and Faulting Together

At one spectacular exposure along the wall of Ophir Chasma, we could actually trace rock layers through a wrinkle ridge. The layers show clear folding—they're bent into an asymmetric arch (what geologists call an anticline). Small thrust faults cut through the folded layers, and you can see how the faults correspond to little steps in the ridge topography.

This site beautifully illustrates that wrinkle ridge formation isn't just about faulting or just about folding—it's an intimate combination of both processes working together.

Polarity Changes Along Strike

Another fascinating observation: some wrinkle ridges actually change character along their length. A ridge might have a steep eastern slope in one area, then switch to having a steep western slope further along. These polarity changes correspond to changes in which fault system is doing most of the work. Where the dominant thrust changes direction, so does the asymmetry of the ridge.

What This Means: Testing Formation Models

For decades, planetary scientists have proposed various models for how wrinkle ridges form. Our subsurface observations allowed us to test which models actually match reality.

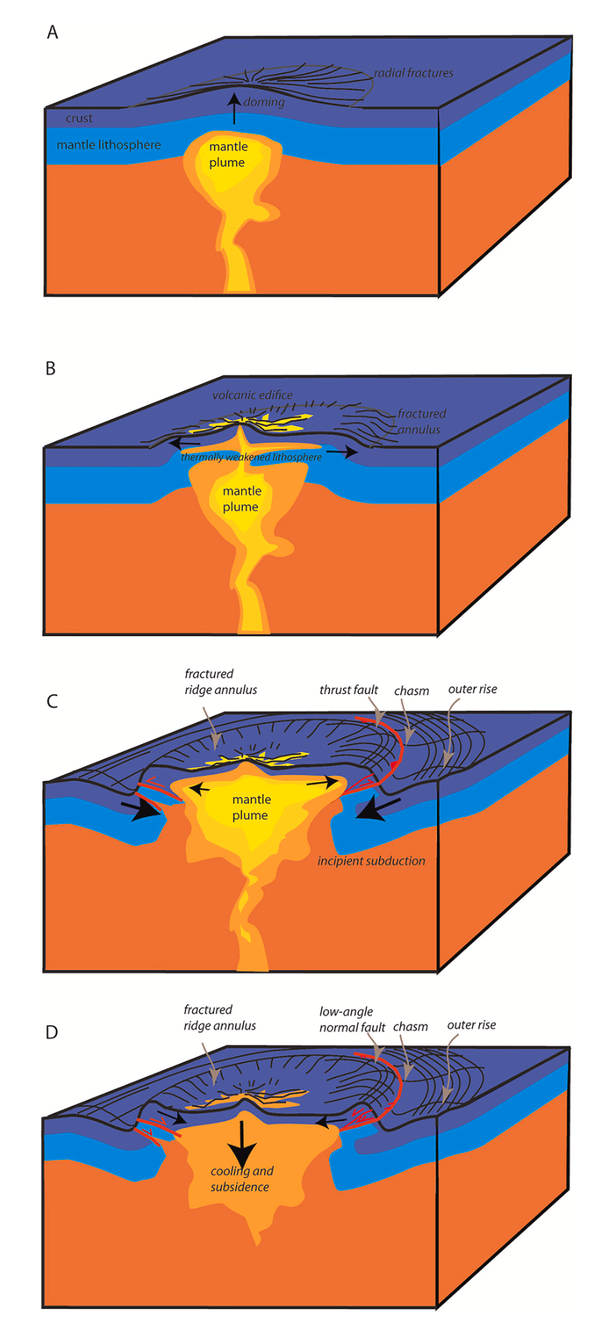

Simple Buckling: Doesn't Fit

The simplest idea—that wrinkle ridges are just buckled layers of rock, like a bent sheet of paper—doesn't explain what we see. The clear presence of major thrust faults cutting through the structure rules out simple elastic bending.

Fault-Bend Folds: Unlikely

Another model suggests wrinkle ridges form as "fault-bend folds"—folds that develop where faults have a flat-ramp-flat geometry. This model predicts that the main fault should have a shallow dip where it reaches the surface. But we consistently see faults emerging at the surface with steep dips (often around 38°). This mismatch makes fault-bend folding an unlikely explanation for most wrinkle ridges.

Fault-Propagation Folds: Best Match

The observations fit best with fault-propagation fold models. In this scenario, a thrust fault propagates upward from a deeper detachment, but loses displacement as it goes up. The "missing" displacement is accommodated by folding of the overlying rocks. This creates exactly what we observe: an asymmetric fold with a steep forelimb, where a steep reverse fault reaches the surface at the base of the ridge.

One particular variant—the Chester and Chester (1990) two-ramp model—gives an especially good match to the characteristic "stair-stepping" profile many wrinkle ridges display, where a narrower ridge sits asymmetrically on top of a broader swell.

Continuum Mechanics Models: Also Consistent

Numerical models that treat the crust as a continuum (like the elastic dislocation model by Watters, 2004, and the boundary element model by Okubo and Schultz, 2004) also show good agreement with our observations. These models predict many of the features we see: blind thrust faults, backthrusts forming in weak zones, bimodal ridge topography, and the association of thrust faults with the steeper ridge slopes.

The Detachment Question

One of the biggest debates in wrinkle ridge studies is whether these structures are "thin-skinned" or "thick-skinned" deformation.

Thin-skinned means the faults connect to a shallow, nearly horizontal detachment—a weak layer that allows the upper crust to slide independently of what's below. Thick-skinned means faults extend deep into the crust without any significant detachment.

Our observations support thin-skinned deformation, at least for the upper crust. The listric shape of faults—steepening upward from shallower angles at depth—suggests they're connecting to something nearly horizontal below our level of observation.

In my previous study on Lunae Planum, I proposed that this detachment might be located at the base of the permafrost, where trapped liquid water under pressure creates ideal conditions for a weak, easily-sliding layer. The subsurface observations from this study are consistent with that interpretation, though we can't directly observe the detachment zone itself since our exposures only reach 500-1000 meters deep, while the detachment likely sits at 2.5-4 kilometers depth.

Conjugate Faults and Symmetric Ridges

While most wrinkle ridges are asymmetric, a few show more symmetric profiles. At one study site in particular (Area 12), we observed a beautiful system of conjugate reverse faults—two fault systems dipping toward each other at similar angles, meeting at depth. This creates a "pop-up" structure with relatively symmetric slopes on both sides.

The presence of conjugate faults is an important finding because it confirms one of the formation models proposed by earlier researchers (Allemand and Thomas, 1992; Mangold et al., 1998). However, conjugate systems of equal significance appear to be the exception rather than the rule. More commonly, if there are faults on both sides of a ridge, one is dominant while the other is subordinate.

The Role of Impact Craters

An important methodological question: are the structures we observe in crater walls really representative, or has the presence of the crater affected the wrinkle ridge structure?

We can actually answer this fairly confidently. In most cases, the wrinkle ridges clearly postdate the craters—we can see uplift of the crater floors showing that faulting continued after impact. The craters provide viewing windows into pre-existing structures rather than fundamentally altering them.

Some ridges do show slight bending or deflection where they cross craters, but the overall fault patterns and geometries are consistent with what we'd expect for these structures. The reduction in overburden due to the crater cavity might make slip slightly easier, possibly resulting in slightly higher displacement on faults within the crater, but the basic architecture remains representative.

Connecting to Terrestrial Analogs

The structures we observe beneath Martian wrinkle ridges bear strong similarities to features seen in certain fold-and-thrust belts on Earth, particularly the Yakima fold belt in Washington State. There, asymmetric anticlinal ridges formed by fault-propagation folding of Columbia River Basalts—a geological setting quite analogous to the Martian flood basalt plains where most wrinkle ridges occur.

The Yakima folds show similar features: thrust faults reaching the surface at steep angles, folded basalt layers, detachments at depth (though deeper than on Mars), and subsidiary faulting creating complex surface morphology. This terrestrial analog gives us confidence that the fault-propagation fold models we're applying to Mars are reasonable.

Implications for Martian Crustal Structure

What do these observations tell us about Mars more broadly?

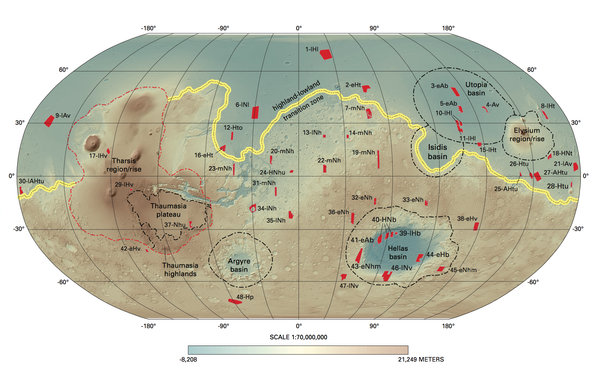

First, they confirm that the Martian crust underwent significant horizontal shortening. The amount varies from place to place—in my Lunae Planum study, I calculated shortening ranging from about 116 meters in areas closer to the Tharsis center to 56 meters further away.

Second, the apparent presence of shallow detachment zones suggests mechanical layering in the Martian crust. You can't have thin-skinned deformation without weak layers that allow decoupling between upper and lower crustal sections.

Third, the fact that we see both brittle faulting and ductile folding occurring together tells us about the mechanical properties and conditions in the upper few kilometers of the Martian crust during the Hesperian period (roughly 3.6-3.9 billion years ago).

Fourth, if the detachment zone really is related to the base of a permafrost layer (as I proposed in my Lunae Planum study), these structures provide indirect evidence for subsurface water distribution on ancient Mars. The depth at which faults flatten out gives us clues about where liquid water might have existed beneath a frozen surface.

Variability is the Norm

If there's one overarching lesson from this study, it's that wrinkle ridges are structurally diverse. While they share common features—thrust faulting, folding, horizontal shortening—the details vary considerably from site to site.

Some ridges are symmetric, most are asymmetric. Some show conjugate faults, most have one dominant system. Fault dips vary from relatively gentle (20-30°) to quite steep (50-60°). Some ridges show clear listric faults, others appear more planar.

This variability probably reflects differences in:

- The properties of the crustal materials being deformed

- The depth and character of weak layers

- The local stress conditions

- The amount of shortening accommodated

- The presence or absence of pre-existing structures

Rather than trying to force all wrinkle ridges into a single formation model, we should recognize that these features formed under a range of conditions and can exhibit a variety of structural styles.

Limitations and Future Work

I should be clear about the limitations of this study. We can only observe the uppermost 500-1000 meters of the wrinkle ridge subsurface. The critical question of whether there's a regional detachment at 3-4 kilometers depth remains beyond our direct observation.

To really distinguish between thin-skinned and thick-skinned deformation, we'd need to see much deeper. Future missions with ground-penetrating radar or seismic capabilities could potentially "see" these deeper structures. The InSight lander has already given us our first detailed seismic data from Mars, and as we get more such data from different regions, we'll be able to build a much more complete picture of Martian crustal structure.

Another limitation is that the faults we observe near the surface might be subsidiary structures rather than the main deep-seated faults. We've tried to focus on the most prominent, throughgoing faults, but there's always some uncertainty about which features are primary and which are secondary.

A Personal Reflection

Mapping faults on Mars is painstaking work. You're looking at grayscale images, trying to trace faint lineations on crater walls, measuring angles from subtle changes in slope, and always second-guessing whether what you're seeing is a real geological structure or an artifact of lighting, image processing, or your own imagination.

But when all the pieces come together—when the fault trace you've mapped on the northern crater wall connects perfectly with the one on the southern wall, when the dip angles you measure match what the kinematic models predict, when the ridge morphology makes perfect sense given the subsurface structure—there's a profound satisfaction in it.

We're reading the tectonic history written in the Martian landscape, deciphering events that happened nearly four billion years ago on a planet we've never visited. Each wrinkle ridge is a story of ancient stresses, of crust responding to enormous forces, of rocks bending and breaking in ways that still leave traces visible from orbit today.

Bringing It All Together

So what's the big picture? Wrinkle ridges on Mars formed through a combination of thrust faulting and folding, driven by horizontal compression of the crust. The structures are dominated by asymmetric fault-propagation folds, where thrust faults propagate upward from deeper detachment zones, creating the characteristic ridge morphology.

The fault patterns are complex, with multiple subsidiary faults creating the wrinkled appearance. Faults typically steepen upward, suggesting they connect to shallower-dipping structures at depth. The observations are most consistent with thin-skinned deformation in the upper crust, though we can't rule out deeper-seated faulting below our level of observation.

The subsurface architecture varies from ridge to ridge, reflecting the diverse conditions under which these features formed. But common threads run through all of them: horizontal shortening, thrust faulting, asymmetric folding, and structural complexity.

Combined with my previous work on Lunae Planum—where I quantified shortening amounts, depths of detachment, and proposed a mechanism involving water-lubricated décollement zones—we now have a fairly complete picture of how these enigmatic features formed and what they tell us about Martian crustal evolution.

The wrinkles on Mars's surface turn out to be anything but superficial. They're evidence of a complex tectonic history, written in faults and folds that we're only now learning to read.

This research was published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters (2022) and builds on my earlier work on Lunae Planum wrinkle ridges published in Icarus (2022). The detailed structural analyses were conducted using high-resolution imagery from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's HiRISE and CTX cameras, combined with elevation data from various Mars orbiter missions.

The study areas included wrinkle ridges at Solis Planum, Nilus Dorsa, Coprates Chasma, Lunae Planum, and Thaumasia Planum—all part of the circum-Tharsis wrinkle ridge system.