A Mysterious Feature on Our Sister Planet

If you could stand on the surface of Venus (ignoring for a moment the crushing atmospheric pressure and 450°C temperatures), you'd see some of the strangest geological features in our solar system. Among the most peculiar are coronae—massive, roughly circular structures that can span hundreds to thousands of kilometers across. They look like giant eyes staring out from the planet's surface, complete with a fractured ridge "eyelid" surrounding a central depression.

Our research team focused on one of the largest and most dramatic of these features: Atahensik Corona, a 700 × 900 kilometer eye-shaped structure in southeastern Aphrodite Terra. What we discovered challenges and refines our understanding of how these enigmatic features form—and reveals that Venus's geological history is far more dynamic than previously thought.

The Challenge: Reading a Planet's History from Orbit

Studying Venus is notoriously difficult. Unlike Mars, where we've landed rovers and can examine rocks up close, Venus's hellish surface conditions make extended surface missions nearly impossible. Instead, we rely on radar imaging from orbiting spacecraft—primarily NASA's Magellan mission from the early 1990s.

The challenge is that radar data from orbit gives you limited resolution compared to what we can see on Mars or Earth. It's like trying to understand a city's layout from grainy aerial photographs taken from a high-flying plane. Despite this limitation, careful analysis can reveal remarkable details about geological structures and their history.

What Makes Atahensik Corona Special?

Atahensik Corona is enormous—about the size of Texas. It has an asymmetric, eye-shaped form with several distinctive features:

- Deep arcuate troughs (chasmata) that curve around the northern and southern sides, plunging as deep as 2,400 meters below the surrounding terrain

- Elevated fractured ridges forming the "rim" of the corona, reaching heights over 6,600 meters

- Broad outer rises that gently swell upward beyond the troughs, forming a peripheral bulge more than 2,000 kilometers in diameter

- A depressed interior where the center has subsided

The whole structure sits within a chain of coronae in eastern Aphrodite Terra and connects to Dali Chasma, a major linear trough system that stretches for hundreds of kilometers.

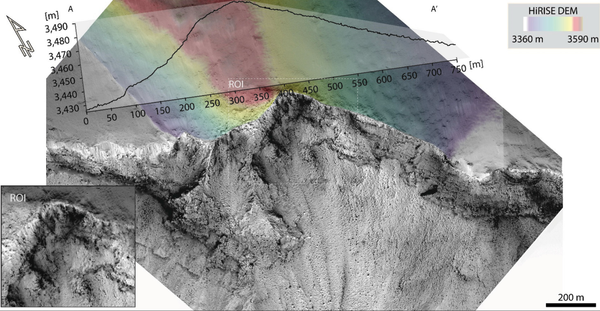

The Breakthrough: Discovering Low-Angle Faults

The key discovery of our research was identifying large-scale fault zones running along the steep inner slopes of Atahensik's arcuate troughs. These faults are remarkable for several reasons:

- They're huge: Extending for hundreds of kilometers along the trough walls

- They're low-angle: Dipping gently (around 22-42°) toward the corona center, rather than steeply

- They expose their fault surfaces: Unusual terrace-like features visible in radar imagery show where the actual fault plane is partially exposed

- They tell a story of reversal: Most remarkably, these faults have a multi-stage history with opposite movements at different times

A Tale of Two Shear Directions

Here's where the story gets really interesting. The evidence shows that these faults formed initially as thrust faults—faults where one block of crust is pushed up and over another, indicating compression. This matches what you'd expect from the overall structure: the asymmetric troughs, the outer rises, and the gravity patterns all suggest the lithosphere was being pushed together and bent downward, like an incipient subduction zone.

But then something changed. The faults were reactivated as low-angle normal faults, where the hanging wall slid downward and exposed parts of the fault plane. This is the opposite sense of motion—it indicates extension rather than compression.

How can we tell? The exposed fault terraces themselves are the smoking gun. In a thrust fault, only the intersection line would be visible at the surface, buried under fault debris. But when a thrust reactivates as a normal fault and the hanging wall slides down, it can expose smooth portions of the underlying fault plane—exactly what we see in the radar images.

Unraveling the Fracture Puzzle

We meticulously mapped and analyzed over 34,741 fracture segments across Atahensik Corona. The pattern that emerged tells a clear chronological story:

- Radial fractures formed first: Radiating outward from the center, these record the initial doming and volcanic activity as a mantle plume rose beneath the area

- Oblique fractures came next: These slightly spiral fractures may record subtle shifts in the plume position

- Concentric fractures formed last: Running parallel to the rim of the outer rise, these formed as the lithosphere bent downward elastically

The outer rise shows particularly clear evidence of this bending—long concentric fractures parallel to the crest line, some forming small grabens (down-dropped blocks). These are classic signatures of extension on the upper surface of a bending plate, exactly like what you see at ocean trenches on Earth.

Learning from Smaller Cousins: Didilia and Pavlova

To understand Atahensik's evolution, we compared it to two smaller coronae in eastern Eistla Regio: Didilia (400 × 450 km) and Pavlova (550 × 650 km). These smaller features lack the deep surrounding troughs of Atahensik but share other characteristics—particularly elevated, heavily fractured central volcanic edifices surrounded by a fractured ridge annulus.

Critically, in both Didilia and Pavlova, the central volcanic mountain is actually higher than the surrounding rim. This is the opposite of Atahensik, where the center has subsided below the rim level.

This comparison suggests an evolutionary sequence: Didilia and Pavlova represent earlier, less mature stages of corona development, while Atahensik shows what happens in the late stages after the volcanic plume cools and the interior subsides.

A Four-Stage Story of Corona Birth and Evolution

Putting all the evidence together, we propose this phenomenological model for how large coronae like Atahensik form:

Stage 1: Initial Uplift and Radial Fracturing

A hot mantle plume rises into the lithosphere, causing thermal uplift and doming of the crust. Radial fractures form evenly across the uplift as magma-filled dikes push toward the surface.

Stage 2: Volcanic Construction and Lateral Spreading

Volcanic activity builds a massive edifice fed by a spreading magmatic reservoir. The weight of this volcanic mountain begins to depress the thermally weakened lithosphere beneath it. The plume spreads laterally at depth, and the outer slopes steepen. This stage is represented by coronae like Didilia and Pavlova, where the central volcano towers above everything else.

Stage 3: Overthrusting and Trough Formation

As the hot plume continues to spread laterally, it encounters cooler, intact lithosphere at its margins. The hot, weak material can't easily push the cold, strong material aside—instead, the fractured ridge annulus begins to thrust outward over the surrounding lithosphere along low-angle thrust faults. This overthrusting causes the cooler lithosphere to bend downward, forming the deep arcuate troughs. As the plate bends, it flexes upward beyond the troughs to form outer rises, where concentric fractures develop at the crest. The topography of the fractured ridge annulus is supported by the doubled-up crust where it's thrust over the intact lithosphere.

Stage 4: Subsidence and Fault Reactivation

Eventually, plume activity decreases and cooling begins. The thermally buoyed interior loses support and begins to subside. The horizontal compressive stresses that drove overthrusting diminish. Now the elevated ridge annulus becomes gravitationally unstable—it's sitting high with no continuing push to support it. The old thrust faults reactivate, but this time as low-angle normal faults, allowing the hanging wall to slide back down and inward, partially exposing the fault planes as terraces.

What About Dali Chasma?

Intriguingly, we found similar low-angle faults with evidence of fault reactivation along Dali Chasma—a relatively straight (rather than arcuate) trough northwest of Atahensik. This suggests that the multi-stage deformation history may not be unique to coronae but could characterize other major trough systems on Venus as well.

Dali Chasma has often been interpreted as a simple extensional rift. Our findings suggest a more complex history: initial formation as a trench with flexural bending and overthrusting, followed by later extension that reactivated the faults.

The Critical Friction Problem

There's a significant mechanical problem here that needs explaining: how do thrust faults—which typically dip around 30°—get reactivated as normal faults?

Under normal circumstances, this shouldn't happen easily. The friction coefficient of most rocks is high enough (around 0.75) that thrust faults would "lock up" before they could slide in the opposite direction. To reactivate them requires either:

- Extremely weak fault zones: Perhaps created by intense grain-size reduction and thermally activated crystal plasticity during prolonged faulting

- Melt lubrication: Frictional melting along the fault plane, creating a thin film that dramatically reduces friction

- High fluid pressures: Though Venus lacks water at its surface, some researchers have proposed that volatiles could exist at depth

On Earth, similar fault reactivations occur where phyllosilicate minerals (clays) or mylonite zones weaken the faults, or where high fluid pressures effectively "float" the overburden. Venus might achieve similar weakening through some combination of thermal effects and possibly small amounts of trapped volatiles.

Reconciling Conflicting Models

For decades, researchers have debated the nature of Venus's chasmata and circumferential troughs. Are they:

- Extensional rifts formed by the planet's surface pulling apart?

- Trenches formed by compression and incipient subduction?

- Vertical adjustments reflecting mantle upwelling and downwelling without significant horizontal motion?

The beauty of our multi-stage model is that it reconciles these seemingly contradictory interpretations. The features formed initially through compression (overthrusting and flexural bending) but were later modified by extension (gravitational collapse and normal faulting). Both models are correct—they just describe different stages in the structure's evolution.

This sequential development mirrors what we see in some terrestrial settings, particularly the Scandinavian Caledonides, where an ancient mountain belt experienced extensional collapse, causing thrust faults to reactivate as low-angle normal faults.

Implications for Venus's Interior and Evolution

Our findings support several key ideas about Venus:

1. Mantle Plumes Drive Corona Formation

The evidence strongly supports models where rising mantle plumes create coronae, though the details of how this happens remain debated. The radial fracturing and volcanic edifices point clearly to focused upwelling.

2. Plume-Induced Incipient Subduction

The thrust faults, asymmetric troughs, outer rises, and gravity patterns all indicate that mantle plumes can indeed trigger incipient subduction at their margins, as proposed by researchers like Sandwell and Schubert in the 1990s and demonstrated experimentally by Davaille and colleagues.

The key is that where hot, weak plume material encounters cold, strong lithosphere, the interface becomes a zone of compression. The fractured corona material thrusts outward over intact lithosphere, which bends downward, creating trench-like features.

3. Dynamic, Evolving Structures

Coronae aren't static features—they evolve through distinct stages over tens of millions of years. The different topographic classes of coronae recognized by researchers likely represent snapshots at different evolutionary stages, from young, active systems (like Didilia and Pavlova) to mature, cooling structures (like Atahensik).

4. Weak Zones in the Lithosphere

The presence of low-angle normal faults requires significant weakening along the fault zones. This weakening might be achieved through thermal softening, melt lubrication, or possibly trapped volatiles—though the exact mechanism remains uncertain.

5. Complex Tectonic History

The multi-stage deformation shows that Venus's tectonic regime can change significantly at local scales. While Venus lacks Earth-style plate tectonics, it clearly experiences complex, evolving deformation patterns associated with mantle plumes.

A Window into Planetary Evolution

The work also provides insights into how rocky planets in general might lose heat and deform when they lack the plate tectonics that so efficiently cools Earth. Venus appears to operate in what some researchers call an "episodic lid" or "plutonic-squishy lid" regime—somewhere between Earth's mobile plates and truly stagnant-lid planets.

The formation and evolution of coronae may represent one of Venus's primary mechanisms for bringing heat from the interior to the surface. The rising plumes, volcanic outpourings, lateral spreading, and eventual collapse all contribute to heat loss.

Looking Forward

Our study was limited by the resolution of 1990s-era Magellan radar data. Future missions will provide much more detailed observations:

- ESA's EnVision mission (planned for the 2030s) will carry VenSAR, a high-resolution radar system

- NASA's VERITAS mission (also planned for the 2030s, though recently delayed) will carry VISAR, an advanced synthetic aperture radar

These missions will be able to image Venus at resolutions comparable to what we have for Mars, potentially revealing fine details of fault structures, fracture patterns, and volcanic features that remain invisible in current data.

Some specific questions these missions might address:

- Can we detect striations or grooves on the exposed fault planes that would confirm our interpretation of their kinematics?

- Are there other large coronae showing similar fault reactivation, or is this specific to Atahensik and its tectonic setting?

- Can we find evidence for the detachment depth where these faults root—perhaps where they connect to a layer of thermally weakened crust or mantle?

- Do smaller coronae show earlier stages of fault development, confirming our evolutionary model?

The Bigger Picture: Comparative Planetology

Studying Venus isn't just about understanding our nearest planetary neighbor—it's about understanding rocky planets as a class. Earth, Venus, and Mars all started with similar building blocks but evolved in dramatically different ways. By studying how Venus's interior heat drives surface deformation, we gain insights into:

- How planets without plate tectonics lose their internal heat

- The role of mantle plumes in planetary evolution

- The conditions under which subduction-like processes can initiate

- The ways volcanic provinces grow and evolve over billions of years

Perhaps most fundamentally, coronae like Atahensik remind us that even "dead" planets (in the sense of lacking plate tectonics) have had remarkably complex geological histories. The multiple stages of fracturing, thrusting, volcanic construction, and eventual collapse recorded at Atahensik occurred over perhaps tens of millions of years—a geological eyeblink, but long enough for dramatic changes in the stress regime and deformation style.

A Personal Note on the Research

One of the satisfying aspects of this research was how comparing coronae of different sizes (Atahensik at 700-900 km, Pavlova at 550-650 km, and Didilia at 400-450 km) revealed the evolutionary sequence. It's like finding fossils of the same species at different ages and being able to reconstruct its life cycle.

The discovery of the exposed fault planes was particularly exciting. In low-resolution data, it would be easy to dismiss the subtle terraces and changes in radar brightness. But when you map them systematically and measure their orientations using stereo topography, a clear pattern emerges: these are real geological structures with consistent geometries extending for hundreds of kilometers.

It's also humbling to realize how much we still don't know. The mechanism for reactivating the faults remains uncertain. The exact depth where the faults root is beyond our ability to observe directly. The thermal structure and composition of the crust and mantle beneath Atahensik are largely mysterious. Future missions will hopefully answer some of these questions, but they'll undoubtedly raise new ones.

Conclusion

Atahensik Corona stands as one of the most spectacular and complex geological features on Venus. Its formation involved:

- Initial plume rise and thermal doming

- Massive volcanic construction

- Lateral plume spreading and steepening of slopes

- Overthrusting of a fractured ridge annulus over intact lithosphere

- Formation of deep troughs and broad outer rises

- Eventual cooling and subsidence of the interior

- Reactivation of thrusts as low-angle normal faults

This four-stage evolutionary sequence, supported by detailed fracture mapping, topographic analysis, and comparison with smaller coronae, provides a unifying framework for understanding these enigmatic features.

The discovery that major fault zones can undergo complete reversal of shear sense—from compression to extension—shows that even without plate tectonics, Venus experiences dynamic and evolving tectonics at local and regional scales. The coronae and troughs aren't static scars but records of planetary evolution, capturing moments in the ongoing thermal history of our sister world.

As we look forward to new Venus missions in the coming decades, Atahensik Corona and features like it will surely yield even more surprises. The exposed fault planes we've identified will be prime targets for high-resolution imaging, potentially revealing details of fault mechanics and deformation that remain invisible in current data.

For now, we can marvel at what these structures tell us: that Venus, despite its hellish surface conditions and lack of plate tectonics, has a geological history as rich and complex as any world in our solar system.

This research was published in Planetary and Space Science by Thomas Kenkmann, Oguzcan Karagoz, and Antonia Veitengruber from the Institute of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Germany.