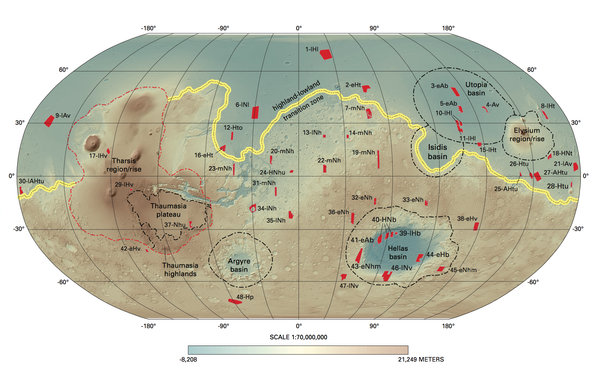

When you look at images of Mars, one of the features you might notice are these long, wavy ridges snaking across the surface. They're called wrinkle ridges, and they're kind of like the stretch marks of a planet - geological scars that tell the story of ancient stresses and strains in the Martian crust.

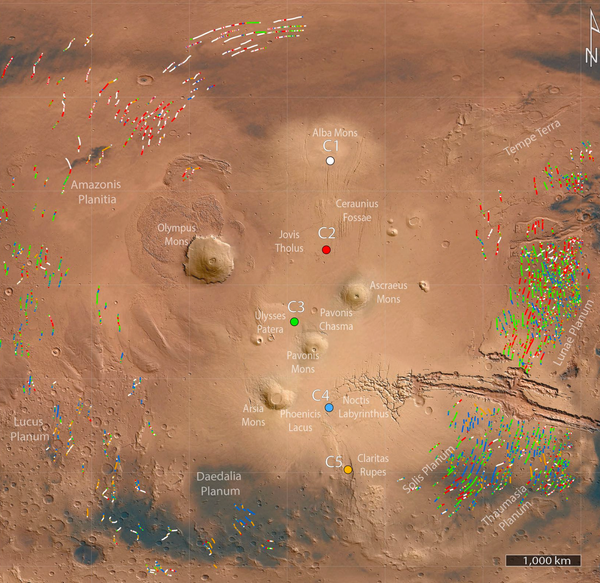

For my recent research, I focused on a region called Lunae Planum, a vast plain on the eastern edge of the Tharsis rise, which is basically a massive volcanic bulge on Mars. Think of Tharsis as a giant dome that pushed up from the planet's surface billions of years ago. And just like when you push up on a blanket, the surrounding material had to respond to that force somehow.

Why Study Wrinkle Ridges?

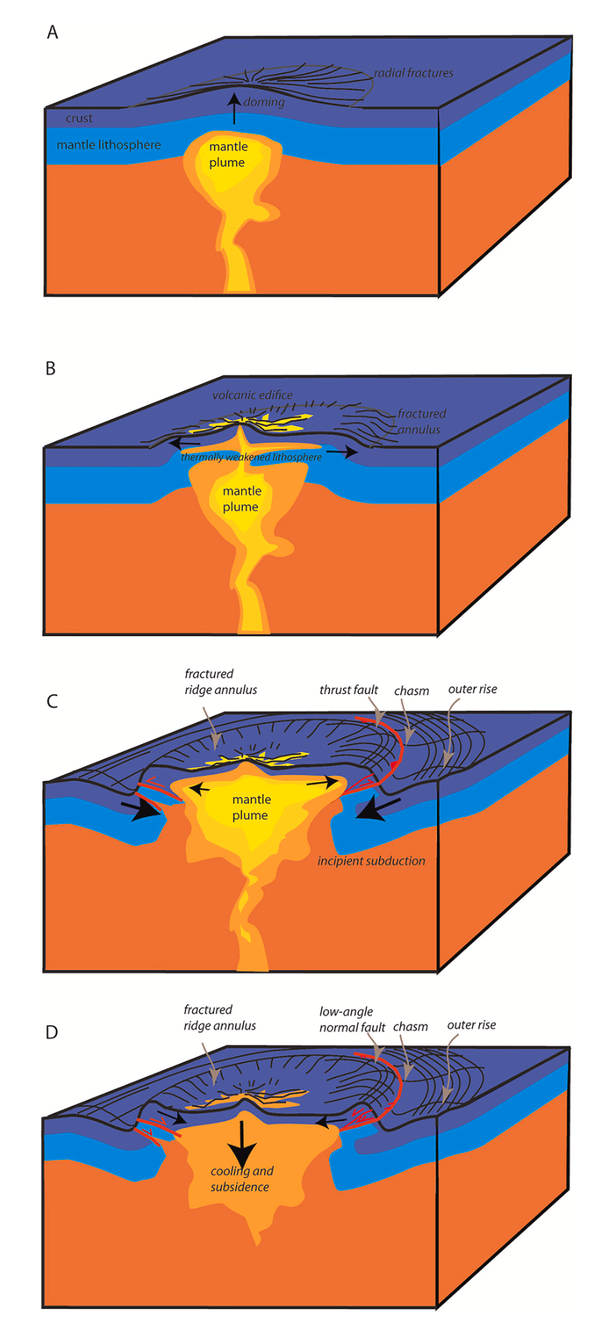

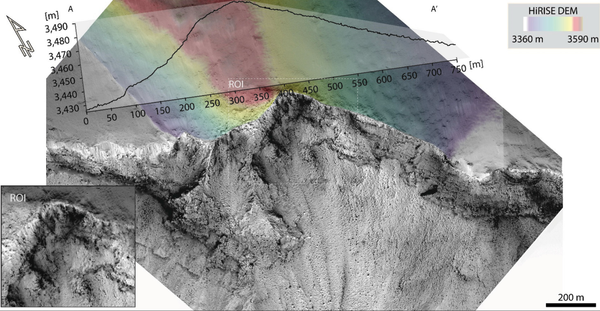

Wrinkle ridges might look like simple bumps from orbit, but they're actually incredibly informative. They form when the crust gets squeezed horizontally, causing rocks to buckle and thrust upward along fault lines. By studying their shape, size, and structure, we can essentially work backward to figure out what was happening deep underground when they formed.

The key questions I wanted to answer were:

- How did these ridges form?

- How much squeezing (or "shortening") did the crust experience?

- How deep do the faults beneath these ridges go?

- What does all this tell us about the structure of Mars's crust?

What I Found

Using high-resolution images and elevation data from Mars orbiters, I analyzed six major wrinkle ridges across Lunae Planum. What immediately jumped out was a clear pattern: the ridges get systematically smaller as you move from west (closer to the Tharsis bulge) to east (farther away).

The westernmost ridge (which I creatively named WR1) stands about 78 meters tall on average and stretches about 5,650 meters wide. The easternmost one (WR6) is only 38 meters tall and 4,300 meters wide. This gradual decrease makes perfect sense - the farther you get from the source of the push (Tharsis), the less dramatic the deformation.

But here's where it gets really interesting. By combining these measurements with kinematic modeling - essentially mathematical models of how rocks fold and fault - I could estimate how much the crust actually shortened. The western part of Lunae Planum experienced about 116 meters of horizontal squeezing, while the eastern part saw only about 56 meters. That might not sound like much for a planetary-scale process, but it's significant.

The Hidden Detachment

One of the most important findings is what lies beneath these ridges. The modeling suggests that the thrust faults creating these ridges don't just plunge straight down into the crust. Instead, they connect to a nearly horizontal "detachment" layer at depth - kind of like how tree roots might spread out along a harder layer of soil.

This detachment rises from about 4 kilometers deep in the west to about 2.6 kilometers deep in the east. The fact that it's tilted very gently toward the Tharsis center is telling. Combined with the gently sloping topography of Lunae Planum, this creates what geologists call a "critical taper" - a wedge shape that's mechanically similar to what you see in mountain belts on Earth.

The Water Connection

Now here's where things get even more interesting. Why would there be a weak detachment layer at exactly this depth? I think water might be the answer.

At 2.6 to 4 kilometers depth on ancient Mars, conditions would have been right for liquid water to exist, sandwiched between frozen permafrost above and solid rock below. This trapped water layer would have been under tremendous pressure from the overlying rock. That pressure would have weakened the rock, making it much easier for faults to slide along this horizon.

This fits beautifully with other evidence from the region. The nearby Kasei Valles, one of Mars's giant outflow channels, cuts down to similar depths. These channels are thought to have formed when pressurized groundwater catastrophically burst out onto the surface. Maybe we're seeing two sides of the same coin - the detachment layer marking an ancient aquifer, and the outflow channels showing where that water eventually escaped.

Why This Matters

This research isn't just about understanding one set of ridges on one Martian plain. It's about piecing together the broader story of how Mars evolved.

First, it shows that Mars had a complex crustal structure with weak layers that could accommodate deformation. This is similar to what we see in fold-and-thrust belts on Earth, like the Zagros Mountains in Iran or the Jura Mountains in Switzerland. The comparison suggests that some fundamental geological processes work similarly across different planets.

Second, it provides concrete evidence for subsurface water on ancient Mars at exactly the depths where we'd expect liquid water to exist based on temperature and pressure conditions. This has implications for understanding Mars's hydrological history and, by extension, its potential for past habitability.

Third, it demonstrates the power of combining detailed observations with mechanical modeling. We can't drill into Mars (yet), so we have to be creative about extracting information from what we can observe at the surface.

The Bigger Picture

Lunae Planum sits at a fascinating transition zone on Mars. To the west is the massive Tharsis volcanic province, dominated by huge shield volcanoes and extensional faulting. To the east is Chryse Planitia, a lowland basin where multiple outflow channels converge. Lunae Planum represents the stressed margin between these two very different regions.

The wrinkle ridges there formed during the Hesperian period, roughly 3.6 to 3.9 billion years ago, when Tharsis was actively growing and loading the lithosphere. The fact that we can still see these features so clearly today speaks to how well-preserved they are - Mars lacks the plate tectonics and active weathering that would have erased such features on Earth long ago.

Looking Forward

There's still so much we don't know. For instance, did the detachment layer form before the ridges, or did water accumulation and the ridge formation happen together? What was the exact composition of the fluids involved - pure water, brines, or something else? How quickly did these ridges form?

Future missions to Mars, especially those that can probe subsurface structure directly (through ground-penetrating radar or seismic studies), will help answer these questions. The InSight lander has already given us our first detailed look at Mars's interior structure through seismic data. As we get more of this kind of information from different regions, we'll be able to build a much more complete picture.

For now, though, those ancient wrinkles on the Martian surface continue to tell their story - of a time when immense volcanic forces squeezed the crust, when liquid water lurked beneath a frozen surface, and when Mars was geologically much more active than the cold, dusty world we see today.

Technical Note

If you're interested in the nitty-gritty details, the full research paper "Circum-Tharsis wrinkle ridges at Lunae Planum: Morphometry, formation, and crustal implications" was published in Icarus (2022). The methodology involved creating high-resolution digital elevation models from Context Camera (CTX) stereo pairs, systematic morphometric analysis of over 500 topographic profiles, and application of fault-propagation fold theory based on the Suppe and Medwedeff models. The key constraint came from measuring exposed fault planes where impact craters and valley walls cut through the ridges, revealing dip angles of 38° ± 5°.

This research was conducted at the Institute of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, Germany, as part of my doctoral work in planetary geology.